An Interview with Goran Bregović

Robert Šoko: John Lennon said once, “Before Elvis there was nothing”. This allegory I used by extension, about you, Goran Bregović, when someone asked me about the pioneers of Balkan music, or better to say, about so-called “international Balkan hype” in the last 30 years. Am I right in saying this?

Goran Bregović: Strangely, Balkan is unknown and undiscovered cultural territory. I think more undiscovered than Africa. It’s strange to say it, but I think that before my music was out, the only thing that Europe or the world knew is “Mystery of Bulgarian Voices”. And that was just thanks to the enthusiasm of one engineer who was working in Bulgaria, who wasn’t a professional musician at all. He brought some recordings of this famous state choir. Two of my Bulgarian singers are from that choir.

So, it was really an incredible miracle that somehow, I was discovered outside. It’s difficult to explain how it happened. You could say it’s because of the movies, but those movies that I did with Kusturica are not commercial movies. They are really for a small group of people. But suddenly I had an audience from Reykjavik to Novosibirsk to Macao…It’s difficult to explain why. I hope that this small window on Balkans would open a little bit through music, so that we can open windows to discover the other things.

Robert Rigney: For instance?

Goran Bregović: For instance we have a writer who won the Nobel Prize, Ivo Andrić. Probably it will come. Because I think that our era is one in which for the first time big cultures are influenced by small ones. Not only in music. In literature, in movies, in cuisine. Suddenly it is possible to discover stuff that is far away. And among these things they discovered me. If you are naïve, you will believe that everything is visible. Which is not true. There are a lot of people that are ready to discover even weirder composers than me. For sure. If I was born fifty years earlier, nothing would have happened.

Robert Rigney: Where do you go from here in Balkan music? There seems to be a lack of new productions.

Goran Bregović: I’ve always been impressed by brass bands. By gypsy brass bands. I remember in my rock & roll times when we had a show in that territory, we would always have a gypsy brass band in our dressing room to play for us before we went on stage. The reason is because with brass bands it is not only about the music. I have always thought that it is near, in aesthetic terms, to early punk.

I think that punk died with the song “God Save The Queen”, which was produced by Chris Thomas, who is the producer of Elton John, because this was the first punk record which was really well-tuned and well-done. And this was the end. Why were we so glued to punk? Because punk brings us a little madness in music, and not only music. It’s the same thing with gypsy brass bands. They don’t play just music. They play madness. Because in the Balkans if it’s just music, it’s not enough. There has to be a touch of madness.

I have a motto on one of my records: “If you don’t go crazy you are not normal.”

Robert Šoko: Who else, beside yourself, should be given a credit for so called “Balkan hype”?

Goran Bregović: I would give credit to klezmer music. Because I worked on one Romanian movie a long time ago, and I had access to archives in Radio Bucharest of klezmer recordings between the First and Second World War. Basically, everything that is played in the Balkans by the Gypsies comes from there. I found all of the aesthetics, a lot of melodies. Of course what makes brass music different from everything else is because, you know in bands normally there is someone who is playing melody and a few of the others who play harmony.

But with brass bands you have freedom within these designated chords, and this is what creates even more madness. Because you have three players who are creating harmony to go around notes. And actually all of aesthetics that attend Balkan music come from klezmer. Because it has this sadness and madness at the same time.

Robert Šoko: What is the magic of Jewish music in the end?

Goran Bregović: I think that this is a bit like us because it is exaggerating. The music is very much exaggerating. We are always exaggerating. In everything. I remember when the fashion was miniskirts, it was really mini to the point where you see pussy. If we are happy, we are too happy. If we are sad, we are too sad. And the music just reflects this.

Robert Šoko: Why do you think this is, that we are always “exaggerating”, often emotionally overdoing things?

Goran Bregović: We are made like this. Who knows? It’s dark territory. During the our five hundred years of shared history with the Ottoman Empire, we were the only direct border in the history of humankind between Orthodox, Catholics and Muslims. There is no other border. Of course, we have this terrible history. And of course, this is why everything we do is like Frankenstein – composed of pieces from other bodies. So, of course, it even starts to be beautiful. You know, Frankenstein is a symbol of ugliness. But probably in the future what we are will be known for beauty.

Robert Rigney: Magnifico said one time that Balkan music is like pizza. You can have tuna fish, olives and pine apple.

Goran Bregović: Yes, and anything goes.

Robert Rigney: You mentioned that Balkan music is like punk. But one of the differences is that punk had the support of the fashion industry. It created a fashion. Balkan didn’t.

Goran Bregović: Big imperial cultures vs. small cultures. Big movements like punk are also local like I am. The only difference is that Anglo-Saxon local is worldwide. And me, I am local, from such a small territory. My language is spoken by like, fifteen million people. So, it is difficult to compare. Of course, we never had a fashion. I remember in high school I had a teacher who was very much impressed by one guy who compiled our first grammar. His name is Vuk Karadžić. And our teacher liked to tell the class how this Vuk Karadžić was big friends with Goethe. They would go out, Karadžić and Goethe in the evening and drink and the day after Goethe started to work on Faust and our guy on the first grammar. So, this gap of one century is still between us and the modern world. So, I try to be a contemporary composer. But my contemporary, if I want to be honest, it goes a way back. Some may think that my music is very old fashioned, of course.

Robert Šoko: You said once that only in France an immigrant could be accepted as an artist too. How come?

Goran Bregović: It’s starting to change. France was accepting, not only our artists for centuries, but political refugees. I don’t know. But they have a long tradition. This is new for the rest of Europe. Now you can see everywhere – in German culture foreigners, from Africans till Turks and Arabs. But France has known this for a very long time, because they have a long history of receiving, I don’t know, Russian refugees and political refugees. I met in Paris in the eighties the daughter for the Shah of Iran. Painters from Spain and artists from Scandinavia. It was always a place of refuge. I said that because at the beginning of the war I was lucky to be in Paris (I was working in the movies). I wasn’t stuck in Sarajevo for four years. And if you look in the first contracts of all the African and Arab artists, West Indian, the first contracts are always French contracts. It’s just like that. This “Mystery Of Bulgarian Voices” I mentioned before was also made in France.

Robert Rigney: I was wondering if you could share a fond memory of Sarajevo.

Goran Bregović: There are some unexplainable connections people have to the place thy were born. I don’t know how you explain such a connection. Sarajevo is a small town and normally it would be a town to escape from. But somehow it has a glue. I can say I am healed from Sarajevo but not till the end.

I still am often going to Sarajevo. Mainly in the winter in the mountain of Jahorina. I tried a couple years ago to move all my production there, but I couldn’t find the infrastructure, the musicians and assistants, so I came back to Belgrade. It’s more practical for me in Belgrade.

Robert Šoko: Recently I saw an interview on a Bosnian TV with you and a TV presenter, it was a blond girl, she asked you about Sevdah. I found your reaction rather interesting. Basically you said I didn’t like sevdah?

Goran Bregović: I like all music, actually. But sevdah, these so called starogradske songs, are not really my cup of tea, which is a provincial version of Istanbul town music. Originally it is music without harmony. It’s just melody and rhythm. But unfortunately our sevdah today comes to the point where they put harmony with it. I don’t know.

I remember once from Sarajevo airport I took a taxi to go to my apartment in Sarajevo. And in the middle of our cab drive, the driver said, “What do you think about sevdah?” And I didn‘t really know what to answer for in Sarajevo it’s difficult, you never know who will take things in a wrong way. However, the taxi driver helped out by telling me how this new sevdah, in his opinion, feels like as if he would now drive backwards all the way from the airport to my place. On the side-walk…

Robert Šoko: Last week I spoke with Dr. Nele Karajlić, the grounding father of New Primitives. What is your take on New Primitives? Nevertheless, you guys are from the same town, same generation, same Sarajevo streets and I always wanted to know your opinion of the movement.

Goran Bregović: You know, I was at their concerts long before they became known. Because they played in small halls, in the first Gymnasium where I was. So, I have known them from the very, very beginning. And it was, I think, important.

Rock & roll in the communist part of the world was more important that in the West. It was like a religion – not music – in communist countries. Maybe not musically. It was not a big deal, our rock & roll. But as a social phenomenon it was really important, because it was kind of subversive in a good way. New Primitives were really important, socially. Musically, honestly, it was not a big deal. But as a social phenomenon it was really important.

Robert Rigney: The music producer, Marko J. Konj told me in an interview that in his opinion punk music and rock & roll in the former Yugoslavia was the music of the establishment – music played by the children of the apparatchiks – whereas narodna, or folk was the real rock & roll lifestyle in Serbia.

Goran Bregović: Of course, our authentic music was not rock and roll. It’s ridiculous to say that. But why my band was that successful – we sold millions of records – because it was inspired by – like the music I am creating today – very much by traditional music. But saying that rock & roll in Yugoslavia was organized by the state is ridiculous. I was the biggest star there, and I didn’t even want to know anyone in the establishment. I remember I had one record where I had the singer in the first part, like President Tito in a white uniform and in the second part, like a guardian of a concentration camp, in black. From today’s point of view it is a little bit childish, you know. But back then it was important for everyone to leave little traces behind, during that time. But of course, you try to avoid going to jail.

For this one record, I composed one song – Ružica – for a forbidden singer from Croatia, Vice Vukov and on the way back from Zagreb. I also met one painter, who painted very famous paintings of the guys on a bench in a park with the newspaper, Politika, over their head, and he told me, “You are young. Do not go too far and spoil your life.”

My manager was arrested at the airport. It was not a pleasant situation. But of course, everyone tried to leave little traces. It was important. It wasn’t because I wanted to demolish communism. I was a communist.

My family was communist. I studied philosophy. At the time you finish you are a Professor of Marxism. So, by profession I am a Professor of Marxism. But I think it was good to be subversive in a good way. And the music did just that. But saying that it was state organized – no, no it’s ridiculous to say that. Of course, there are some kids who want to sing, but everyone wants to sing.

Robert Šoko: One of the quotes from you, that helped me a lot in life was when someone asked you, “Who disappointed you the most?” you said, “friends.”

Goran Bregović: It’s mainly because of the war. Human beings are conditioned. If you condition them in some way, they will be that way. This sentence was probably right after the war.

Robert Šoko: Speaking of music, Goran, and now we have thirty years of this Balkan hype, which is slowly subsiding, slowly becoming less interesting for DJ‘s. We were never mainstream, but at some point, there was a hype. In the zero years and the 10s Balkan music and Balkan parties was hip. What do you think, what is going to happen now?

Goran Bregović: Well, what is good it will be left. If not, it will pass. It is like everything else. You know, this is not a big culture. It’s an invisible culture. In every sense. You can buy the biggest book of the history of music. There will be nobody there. Probably I will be the first one there. It’s already huge that we were fashionable in one moment. But I don’t know – still in South America a lot of DJs work on it. I know some good DJs who work with Balkan music.

What’s good about DJ in Balkan music – you know, in our music, its baroque – how do you say it? It’s exaggerated. Everything is too much. And then on the way, the DJs simplify, because they need to simplify things. And on the way back, I see that our musicians are trying to simplify the things they did before. I think that this action and reaction was quite useful.

Robert Šoko: Speaking of DJs, what you think, for example, about Shantel?

Goran Bregović: He was important because he was a guy who was on top charts with Balkan music. It doesn’t matter if it’s not from the Balkans. Gershwin wasn’t black but he left behind him the most important jazz opera. So it means nothing.

Robert Rigney: What about Balkan Beat Box?

Goran Bregović: Well, we played once in a beautiful place in Israel and we played together. You might say they are DJs and not big musicians. But they were quite good. We were jamming together nicely.

Robert Rigney: Now the new flavor of the month appears to be Turkish.

Goran Bregović: Istanbul is magnificent. It is like London. Five centuries of the best of everything was accumulating in Istanbul. In Istanbul you will find the essence of everything that belonged to the Ottoman Empire for five centuries. I remember when I produced Sezan Aksu, I loved so much to play with Turkish musicians. This is so fucking top class. Because it is a big imperial town. They live on accumulated beauty for five centuries that was half of the world. You can see in Istanbul miracles that you cannot see anywhere else.

Robert Rigney: Apropos Istanbul, maybe you can say something about working with Sezen Aksu.

Goran Bregović: I had some luck to produce some good artists from the Balkans. And also with Sezan Aksu. I remember when they called me to produce her. So I said, OK. I was curious of course. And it appeared her manager was a professor of French. You know, we have some stereotypes that you grow up with. Like stereotypes of Germany, stereotypes of Turks. This guy was a highly educated gentleman. I was in London working on some British movie at the time. I was at the hotel and they called from the reception, there is one Madame Sezen Aksu, who wants to see you. I said okay. In two minutes someone opened the door, and she was in the door, while I was still in bed. And she came to me bed, took off the blankets, she took down my pants to see my dick. And she said, “It’s okay.” Lucky I have a big dick.

Robert Rigney: What do you have to say to your critics who say you have taken melodies without giving due credit, etc. etc.?

Goran Bregović: There is no serious composer of music in history who was not inspired by tradition. Stravinsky, Lennon and McCartney, Bono – they came from tradition, what else? Music is the first human language. Human beings were communicating with music before any language, before any religion, before anything else. This is why you cannot cheat with music.

You can write like Salmon Rushdie – he writes in English. Or Milan Kundera – he writes in French. But music you cannot cheat. You cannot translate. It has to go from this place where it is. The deepest place that there is. The most metaphysical communication that we have. This is the most important mobile phone that we have in us. What else do you have if you want to speak this deep language then to come from this strong tradition. It’s not rational. It’s ridiculous, this whole thing. It means nothing, this critique. If it would be that simple, everyone would be like me. Or like Stravinsky. But it’s not that simple.

Robert Šoko: I come from a similar background as you. Father Croat, mother Serb. And my wife is a French Arab, yours is a Bosnian Muslim. How do you make sense of this dichotomy?

Goran Bregović: You have to be in dialogue, always. I have a new record that came out a week ago. Bellybutton of the World. I was commissioned to wrote one violin concerto for the Orchestra National in France. And the violin is played in three main manners. In the Christian manner – how you play classical music – klezmer, how Jews play, which is quite different – and Oriental, which is how Muslims play, which is a completely different technique. So I wrote one violin concerto for three violinists who come from those three traditions. And this is how I deal with those kinds of things. I have in me all of this mix of stuff, which something just goes out.

Robert Šoko: You also have a rock musician in you.

Goran Bregović: I had in my last album a Serbian nationalist forbidden song and a Croat nationalist forbidden song. And if you know what it is all about then you see that something is wrong. I did something similar with Dalaras in Greece. It’s as though it’s always been there together. So this is how I deal with this genetic hysteria.

Robert Rigney: Despite the symphonic nature of this Album, aren’t you also looking for a new hit?

Goran Bregović: No. I have had these kinds of commissions in the last thirty years. I love it. I was commissioned by the Vatican, etc. etc. There have been a lot of these kinds of things written in the last twenty or thirty years as commissions. And I love commissions. It’s not by chance that such a huge part of the history of art is owing to commissions. Without commissions we wouldn’t have Shakespeare, we wouldn’t have Mozart, Michelangelo. It’s good to have commissions. You have some kind of field that has borders.

This kind of freedom is human freedom. Freedom isn’t just to do everything. You need constraints. Then you have the deadline it has to be finished by, which is very important for an artist. If you don’t have it you can keep on going endlessly. And you are paid. So it’s very good altogether. And I was commissioned for that.

And at that time I found one story on the internet.

It said that one reporter from CNN heard about one old Jew who for years and years everyday at the same time was standing in front to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. And the reporter decided to do a story so she went to the Wall and found the man, and waited till the end of his praying and she said, “You are in front of this Wall trying to talk to God.”

And he said, “Yes, for sixty years.” “And what are you praying for?” she asked. “I am praying that all of these wars between Christians, Muslims and Jews are ending so that at least our kids can live together,” he said. And she said, “And after all of these years praying in front of this wall, what is your conclusion?”

And he said, “I have the impression that I am talking to a wall.”

So, if there is something to learn from these stories it is that obviously God didn’t schedule us to live together. This is something that we will have to learn by ourselves. So as an artist, it is easy for me to put something together that is unimaginable for politicians of our religions. Of course, you are not going to change the world with a piece of music, but maybe you will change somebody, and if you do that that is an achievement.

—————————————-

Copyrights © Robert Rigney & Robert Šoko | Interviewed 22. June 2023, Berlin

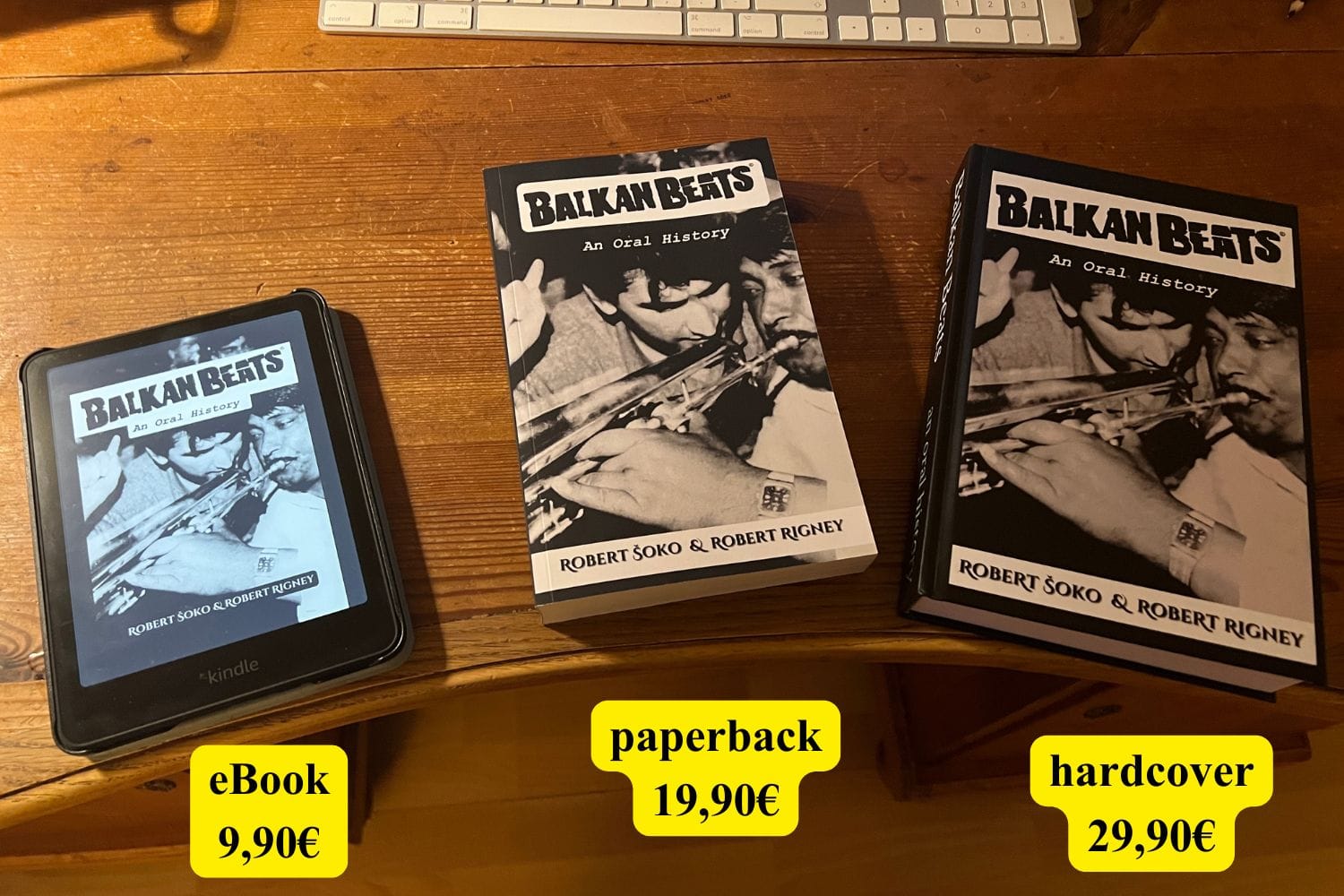

This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book.

Goran Bregović (born 1950 in Sarajevo, Bosnia) is a recording artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina. He is one of the most internationally known modern musicians and composers of the Slavic-speaking countries in the Balkans, and is one of the few former Yugoslav musicians who has performed at major international venues such as Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall and L’Olympia.

Source Wikipedia

“Talking to a wall” – an Interview with Goran Bregović

by Robert Rigney & Robert Šoko, Berlin 2023

Robert Šoko: John Lennon said once, “Before Elvis there was nothing”. This allegory I used by extension, about you, Goran Bregović, when someone asked me about the pioneers of Balkan music, or better to say, about so-called “international Balkan hype” in the last 30 years. Am I right in saying this?

Goran Bregović: Strangely, Balkan is unknown and undiscovered cultural territory. I think more undiscovered than Africa. It’s strange to say it, but I think that before my music was out, the only thing that Europe or the world knew is “Mystery of Bulgarian Voices”. And that was just thanks to the enthusiasm of one engineer who was working in Bulgaria, who wasn’t a professional musician at all. He brought some recordings of this famous state choir. Two of my Bulgarian singers are from that choir. So, it was really an incredible miracle that somehow, I was discovered outside. It’s difficult to explain how it happened. You could say it’s because of the movies, but those movies that I did with Kusturica are not commercial movies. They are really for a small group of people. But suddenly I had an audience from Reykjavik to Novosibirsk to Macao…It’s difficult to explain why. I hope that this small window on Balkans would open a little bit through music, so that we can open windows to discover the other things.

Robert Rigney: For instance?

Goran Bregović: For instance we have a writer who won the Nobel Prize, Ivo Andrić. Probably it will come. Because I think that our era is one in which for the first time big cultures are influenced by small ones. Not only in music. In literature, in movies, in cuisine. Suddenly it is possible to discover stuff that is far away. And among these things they discovered me. If you are naïve, you will believe that everything is visible. Which is not true. There are a lot of people that are ready to discover even weirder composers than me. For sure. If I was born fifty years earlier, nothing would have happened.

Robert Rigney: Where do you go from here in Balkan music? There seems to be a lack of new productions.

Goran Bregović: I’ve always been impressed by brass bands. By gypsy brass bands. I remember in my rock & roll times when we had a show in that territory, we would always have a gypsy brass band in our dressing room to play for us before we went on stage. The reason is because with brass bands it is not only about the music. I have always thought that it is near, in aesthetic terms, to early punk.

I think that punk died with the song “God Save The Queen”, which was produced by Chris Thomas, who is the producer of Elton John, because this was the first punk record which was really well-tuned and well-done. And this was the end. Why were we so glued to punk? Because punk brings us a little madness in music, and not only music. It’s the same thing with gypsy brass bands. They don’t play just music. They play madness. Because in the Balkans if it’s just music, it’s not enough. There has to be a touch of madness.

I have a motto on one of my records: “If you don’t go crazy you are not normal.”

Robert Šoko: Who else, beside yourself, should be given a credit for the so called “Balkan hype”?

Goran Bregović: I would give credit to klezmer music. Because I worked on one Romanian movie a long time ago, and I had access to archives in Radio Bucharest of klezmer recordings between the First and Second World War. Basically, everything that is played in the Balkans by the Gypsies comes from there. I found all of the aesthetics, a lot of melodies. Of course what makes brass music different from everything else is because, you know in bands normally there is someone who is playing melody and a few of the others who play harmony.

But with brass bands you have freedom within these designated chords, and this is what creates even more madness. Because you have three players who are creating harmony to go around notes. And actually all of aesthetics that attend Balkan music come from klezmer. Because it has this sadness and madness at the same time.

Robert Šoko: What is the magic of Jewish music in the end?

Goran Bregović: I think that this is a bit like us because it is exaggerating. The music is very much exaggerating. We are always exaggerating. In everything. I remember when the fashion was miniskirts, it was really mini to the point where you see pussy. If we are happy, we are too happy. If we are sad, we are too sad. And the music just reflects this.

Robert Šoko: Why do you think this is, that we are always “exaggerating”, overdoing things?

Goran Bregović: We are made like this. Who knows? It’s dark territory. During the our five hundred years of shared history with the Ottoman Empire, we were the only direct border in the history of humankind between Orthodox, Catholics and Muslims. There is no other border. Of course, we have this terrible history. And of course, this is why everything we do is like Frankenstein – composed of pieces from other bodies. So, of course, it even starts to be beautiful. You know, Frankenstein is a symbol of ugliness. But probably in the future what we are will be known for beauty.

Robert Rigney: Magnifico said one time that Balkan music is like pizza. You can have tuna fish, olives and pine apple.

Goran Bregović: Yes, and anything goes.

Robert Rigney: You mentioned that Balkan music is like punk. But one of the differences is that punk had the support of the fashion industry. It created a fashion. Balkan didn’t.

Goran Bregović: Big imperial cultures vs. small cultures. Big movements like punk are also local like I am. The only difference is that Anglo-Saxon local is worldwide. And me, I am local, from such a small territory. My language is spoken by like, fifteen million people. So, it is difficult to compare. Of course, we never had a fashion. I remember in high school I had a teacher who was very much impressed by one guy who compiled our first grammar. His name is Vuk Karadžić. And our teacher liked to tell the class how this Vuk Karadžić was big friends with Goethe. They would go out, Karadžić and Goethe in the evening and drink and the day after Goethe started to work on Faust and our guy on the first grammar. So, this gap of one century is still between us and the modern world. So, I try to be a contemporary composer. But my contemporary, if I want to be honest, it goes a way back. Some may think that my music is very old fashioned, of course.

Robert Šoko: You once claimed that only in France could you be accepted as a foreigner but also as an artist. How come?

Goran Bregović: It’s starting to change. France was accepting, not only our artists for centuries, but political refugees. I don’t know. But they have a long tradition. This is new for the rest of Europe. Now you can see everywhere – in German culture foreigners, from Africans till Turks and Arabs. But France has known this for a very long time, because they have a long history of receiving, I don’t know, Russian refugees and political refugees. I met in Paris in the eighties the daughter for the Shah of Iran. Painters from Spain and artists from Scandinavia. It was always a place of refuge. I said that because at the beginning of the war I was lucky to be in Paris (I was working in the movies). I wasn’t stuck in Sarajevo for four years. And if you look in the first contracts of all the African and Arab artists, West Indian, the first contracts are always French contracts. It’s just like that. This “Mystery Of Bulgarian Voices” I mentioned before was also made in France.

Robert Rigney: I was wondering if you could share a fond memory of Sarajevo.

Goran Bregović: There are some unexplainable connections people have to the place thy were born. I don’t know how you explain such a connection. Sarajevo is a small town and normally it would be a town to escape from. But somehow it has a glue. I can say I am healed from Sarajevo but not till the end.

I still am often going to Sarajevo. Mainly in the winter in the mountain of Jahorina. I tried a couple years ago to move all my production there, but I couldn’t find the infrastructure, the musicians and assistants, so I came back to Belgrade. It’s more practical for me in Belgrade.

Robert Šoko: Recently I saw an interview on a Bosnian TV with you and a TV presenter, it was a blond girl, she asked you about sevdah. I found your reaction rather interesting. Basically you said you didn’t like sevdah?

Goran Bregović: I like all music, actually. But sevdah, these so called starogradske songs, are not really my cup of tea, which is a provincial version of Istanbul town music. Originally it is music without harmony. It’s just melody and rhythm. But unfortunately our sevdah today comes to the point where they put harmony with it. I don’t know.

I remember once from Sarajevo airport I took a taxi to go to my apartment in Sarajevo. And in the middle of our cab drive, the driver said, “What do you think about sevdah?” And I didn‘t really know what to answer for in Sarajevo it’s difficult, you never know who will take things in a wrong way. However, the taxi driver helped out by telling me how this new sevdah, in his opinion, feels like as if he would now drive backwards all the way from the airport to my place. On the side-walk…

Robert Šoko: Last week I spoke with Dr. Nele Karajlić, the grounding father of New Primitives. What is your take on New Primitives? Nevertheless, you guys are from the same town, same generation, same Sarajevo streets and I always wanted to know your opinion of the movement

Goran Bregović: You know, I was at their concerts long before they became known. Because they played in small halls, in the first Gymnasium where I was. So, I have known them from the very, very beginning. And it was, I think, important.

Rock & roll in the communist part of the world was more important that in the West. It was like a religion – not music – in communist countries. Maybe not musically. It was not a big deal, our rock & roll. But as a social phenomenon it was really important, because it was kind of subversive in a good way. New Primitives were really important, socially. Musically, honestly, it was not a big deal. But as a social phenomenon it was really important.

Robert Rigney: The music producer, Marko J. Konj told me in an interview that in his opinion punk music and rock & roll in the former Yugoslavia was the music of the establishment – music played by the children of the apparatchiks – whereas narodna, or folk was the real rock & roll lifestyle in Serbia.

Goran Bregović: Of course, our authentic music was not rock and roll. It’s ridiculous to say that. But why my band was that successful – we sold millions of records – because it was inspired by – like the music I am creating today – very much by traditional music. But saying that rock & roll in Yugoslavia was organized by the state is ridiculous. I was the biggest star there, and I didn’t even want to know anyone in the establishment. I remember I had one record where I had the singer in the first part, like President Tito in a white uniform and in the second part, like a guardian of a concentration camp, in black. From today’s point of view it is a little bit childish, you know. But back then it was important for everyone to leave little traces behind, during that time. But of course, you try to avoid going to jail.

For this one record, I composed one song – Ružica – for a forbidden singer from Croatia, Vice Vukov and on the way back from Zagreb. I also met one painter, who painted very famous paintings of the guys on a bench in a park with the newspaper, Politika, over their head, and he told me, “You are young. Do not go too far and spoil your life.”

My manager was arrested at the airport. It was not a pleasant situation. But of course, everyone tried to leave little traces. It was important. It wasn’t because I wanted to demolish communism. I was a communist.

My family was communist. I studied philosophy. At the time you finish you are a Professor of Marxism. So, by profession I am a Professor of Marxism. But I think it was good to be subversive in a good way. And the music did just that. But saying that it was state organized – no, no it’s ridiculous to say that. Of course, there are some kids who want to sing, but everyone wants to sing.

Robert Šoko: One of the quotes from you, that helped me a lot in life was when someone asked you, “Who disappointed you the most?” you said, “friends.”

Goran Bregović: It’s mainly because of the war. Human beings are conditioned. If you condition them in some way, they will be that way. This sentence was probably right after the war.

Robert Šoko: Speaking of music, Goran, and now we have thirty years of this Balkan hype, which is slowly subsiding, slowly becoming less interesting for DJ‘s. We were never mainstream, but at some point, there was a hype. In the zero years and the 10s Balkan music and Balkan parties was hip. What do you think, what is going to happen now?

Goran Bregović: Well, what is good it will be left. If not, it will pass. It is like everything else. You know, this is not a big culture. It’s an invisible culture. In every sense. You can buy the biggest book of the history of music. There will be nobody there. Probably I will be the first one there. It’s already huge that we were fashionable in one moment. But I don’t know – still in South America a lot of DJs work on it. I know some good DJs who work with Balkan music.

What’s good about DJ in Balkan music – you know, in our music, its baroque – how do you say it? It’s exaggerated. Everything is too much. And then on the way, the DJs simplify, because they need to simplify things. And on the way back, I see that our musicians are trying to simplify the things they did before. I think that this action and reaction was quite useful.

Robert Šoko: Speaking of DJs, what you think, for example, about Shantel?

Goran Bregović: He was important because he was a guy who was on top charts with Balkan music. It doesn’t matter if it’s not from the Balkans. Gershwin wasn’t black but he left behind him the most important jazz opera. So it means nothing.

Robert Rigney: What about Balkan Beat Box?

Goran Bregović: Well, we played once in a beautiful place in Israel and we played together. You might say they are DJs and not big musicians. But they were quite good. We were jamming together nicely.

Robert Rigney: Now the new flavor of the month appears to be Turkish.

Goran Bregović: Istanbul is magnificent. It is like London. Five centuries of the best of everything was accumulating in Istanbul. In Istanbul you will find the essence of everything that belonged to the Ottoman Empire for five centuries. I remember when I produced Sezen Aksu, I loved so much to play with Turkish musicians. This is so fucking top class. Because it is a big imperial town. They live on accumulated beauty for five centuries that was half of the world. You can see in Istanbul miracles that you cannot see anywhere else.

Robert Rigney: Apropos Istanbul, maybe you can say something about working with Sezen Aksu.

Goran Bregović: I had some luck to produce some good artists from the Balkans. And also with Sezen Aksu. I remember when they called me to produce her. So I said, OK. I was curious of course. And it appeared her manager was a professor of French. You know, we have some stereotypes that you grow up with. Like stereotypes of Germany, stereotypes of Turks. This guy was a highly educated gentleman. I was in London working on some British movie at the time. I was at the hotel and they called from the reception, there is one Madame Sezen Aksu, who wants to see you. I said okay. In two minutes someone opened the door, and she was in the door, while I was still in bed. And she came to me bed, took off the blankets, she took down my pants to see my dick. And she said, “It’s okay.” Lucky I have a big dick.

Robert Rigney: What do you have to say to your critics who say you have taken melodies without giving due credit, etc. etc.?

Goran Bregović: There is no serious composer of music in history who was not inspired by tradition. Stravinsky, Lennon and McCartney, Bono – they came from tradition, what else? Music is the first human language. Human beings were communicating with music before any language, before any religion, before anything else. This is why you cannot cheat with music.

You can write like Salmon Rushdie – he writes in English. Or Milan Kundera – he writes in French. But music you cannot cheat. You cannot translate. It has to go from this place where it is. The deepest place that there is. The most metaphysical communication that we have. This is the most important mobile phone that we have in us. What else do you have if you want to speak this deep language then to come from this strong tradition. It’s not rational. It’s ridiculous, this whole thing. It means nothing, this critique. If it would be that simple, everyone would be like me. Or like Stravinsky. But it’s not that simple.

Robert Šoko: I come from a very similar national background as you: father Croat, mother Serb. My wife is a French Arab, yours is a Bosnian Muslim. How do you, or how “do we” make sense of this national dichotomy?

Goran Bregović: You have to be in dialogue, always. I have a new record that came out a week ago. Bellybutton of the World. I was commissioned to wrote one violin concerto for the Orchestra National in France. And the violin is played in three main manners. In the Christian manner – how you play classical music – klezmer, how Jews play, which is quite different – and Oriental, which is how Muslims play, which is a completely different technique. So I wrote one violin concerto for three violinists who come from those three traditions. And this is how I deal with those kinds of things. I have in me all of this mix of stuff, which something just goes out.

Robert Šoko: You also have a rock musician in you.

Goran Bregović: I had in my last album a Serbian nationalist forbidden song and a Croat nationalist forbidden song. And if you know what it is all about then you see that something is wrong. I did something similar with Dalaras in Greece. It’s as though it’s always been there together. So this is how I deal with this genetic hysteria.

Robert Rigney: Despite the symphonic nature of this Album, aren’t you also looking for a new hit?

Goran Bregović: No. I have had these kinds of commissions in the last thirty years. I love it. I was commissioned by the Vatican, etc. etc. There have been a lot of these kinds of things written in the last twenty or thirty years as commissions. And I love commissions. It’s not by chance that such a huge part of the history of art is owing to commissions. Without commissions we wouldn’t have Shakespeare, we wouldn’t have Mozart, Michelangelo. It’s good to have commissions. You have some kind of field that has borders.

This kind of freedom is human freedom. Freedom isn’t just to do everything. You need constraints. Then you have the deadline it has to be finished by, which is very important for an artist. If you don’t have it you can keep on going endlessly. And you are paid. So it’s very good altogether. And I was commissioned for that.

And at that time I found one story on the internet.

It said that one reporter from CNN heard about one old Jew who for years and years everyday at the same time was standing in front to the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem. And the reporter decided to do a story so she went to the Wall and found the man, and waited till the end of his praying and she said, “You are in front of this Wall trying to talk to God.”

And he said, “Yes, for sixty years.” “And what are you praying for?” she asked. “I am praying that all of these wars between Christians, Muslims and Jews are ending so that at least our kids can live together,” he said. And she said, “And after all of these years praying in front of this wall, what is your conclusion?”

And he said, “I have the impression that I am talking to a wall.”

So, if there is something to learn from these stories it is that obviously God didn’t schedule us to live together. This is something that we will have to learn by ourselves. So as an artist, it is easy for me to put something together that is unimaginable for politicians of our religions. Of course, you are not going to change the world with a piece of music, but maybe you will change somebody, and if you do that that is an achievement.

Copyrights © Robert Rigney & Robert Šoko | Interviewed 22. June 2024, Berlin

This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book.