Interview with Amira Medunjanin

By Robert Rigney 2024

How did it come about that your English is so perfect?

I don’t know. I picked it up over the years. I worked for the British military service in Croatia. And before that, I worked for UNPROFOR, and then I worked for the European Commission for twelve years. So basically, it was the official language.

You speak with a very distinct British accent.

Yes, it’s because I worked with them for quite some time. I picked it up. That’s what people say about singers; They pick up the accents very easily. Because I have spent most of my time with Brits, you know. Yeah, so it’s stuck with me.

Where are you located at the moment?

I am in Sarajevo at the moment. Actually, I am between two countries. I live in Croatia and in Bosnia. I live in a small city in Istria, on the coast. But since this pandemic has started, I have been spending more time with my parents here. So it’s sort of like I am being torn between two words. But I was born in Sarajevo. I come from here.

What was it like growing up in Sarajevo?

It’s a typical small part of Sarajevo, where all of the houses are so close they are almost attached to each other. We call it mahalle. Growing up in Sarajevo was very special in so many ways. It’s a special place. It’s a special city. Nowadays it is very different to what it used to be when I was a kid. Still, some of the old remain, especially in the old part of town. When I say, mahalle, I mean everyone knows everyone. If you want to have a coffee with a neighbor, you don’t have to call in advance. They just pop in the door.

It’s still that way.

In my neighborhood it is. Not many people who were born in Sarajevo remained here, unfortunately. But you can still find the old way, and that’s what I like about it. It’s very open and very free. You walk down the pavement of your block, you can smell the different kinds of cuisine coming from the open windows. I like that closeness. When I think of my childhood I recall the smells, among other things. And of course, the music coming from all of the houses. It was always like that: open doors and open windows when the weather is nice and sunny spilling music. I have more memories of the sunny days than the winter.

Amira is a Muslim name. Do you define yourself as such?

I’m a Bosnian. Born in Sarajevo. But yeah, my name is Muslim. I come from a Muslim family. But you see, when it comes to the feeling where you belong to, I always say that I am a Bosnian. And Sarajevo is in Bosnia. So I am always a Bosnian and a Herzegovinian, whatever that is.

What was Sarajevo like in terms of music before the war?

Sarajevo was a Mecca musically. Many fantastic bands come from this city and musicians in general. Not just bands, but individual singers. It was like a cradle of music. Many people said that if you could win over the audience in Sarajevo, you could make it anywhere. Sarajevo was really very strong when it came to the music scene. Seventies, eighties – that was the time. Especially when the New Wave started. Everyone was pushing to achieve his or her place in the music scene. It was so rich and beautiful. All sorts of different bands were emerging. It was a different time than today. We all grew up on very good music. I’m pretty lucky to be able to say that.

What were you listening to back then specifically?

Well, besides sevdah, which is really a part of my culture, part of my nature and part of me, I listened to all sorts of music. As a teenager I was really into punk, and I still am. Maybe my hair proves that. I was totally crazy about – I have said this so many times – but I really loved Nick Cave and his writing. Especially his poems and his way of bringing music to people. He’s not bound to any trend. He goes his own way, and I really admire him for that. Aside from that, local bands, like Ekaterina Velika from Belgrade and Azra from Zagreb, Leb i Sol, a brilliant band from Macedonia. I listened to all that kind of music. The Beatles were something you had to know. I was encouraged to know everything about the Beatles. So when it comes to the music that was shaping me through my childhood and the later years, it was coming from everywhere. I sometimes reach for classical music as well; it’s very relaxing. But I can say that I am the child of New Wave.

Did you ever listen to Bijelo Dugme?

Oh, yeah. I sing some of their songs on my concerts. I find this stuff interesting, although they say I am a sevdah singer. So, I prefer not to be labeled that.

What sort of musical environment did you grow up in at home?

It was more sevdah. My mom is totally in love with that music. She was actually the one who helped me understand the songs. I would sing as a child and she would correct me if I was wrong in certain parts. She was my first audience. At home we were really listening a lot to sevdah. Especially on the radio. It was very popular. I still listen to radio a lot. It’s my preferred media.

Do they play a lot of traditional stuff on Bosnian radio stations?

Yeah, there are various radio stations. Back in the old days, in the eighties, Radio Sarajevo was a good radio station. They were also organizing a lot of auditions for emerging singers, especially sevdah singers. It was a quite lovely educational climate, growing up in Sarajevo.

Did you have any ambitions to be a singer prior to the war?

I didn’t really. If I had any ambitions, I would have gone to music school. I don’t read music. I can’t read scores and stuff like that. So I am basically a self-taught musician. I never thought about adopting music as a profession. Because music is something – I don’t know quite how to put it – sacred in a way. I don’t see myself as a professional nowadays, although I live off of music and make a living from singing. I’m just fortunate to do something that is precious, not just for me, but for so many people. And then to be able to live off of that, is truly a blessing. You know what I mean? But no, as a kid, and in my younger days, I never had any aspirations. I studied something completely different: economics.

How did you experience the war and the siege of Sarajevo?

I can tell you that I almost never, ever talk about it. I was here, and I survived and that’s it. It was something that I wouldn’t wish upon anyone. It’s not that I don’t like talking about it. It’s just that I am trying to – not to forget (you can’t forget it). You know, it’s very strange. A lot of people ask me about it. I don’t even know how it was or how we survived. I have no idea how I survived. Out of pure luck, I suppose.

You can identify with what is going on now in Ukraine, I’d imagine; the images must hit home.

In general, I despise the very idea of violence. What we went through in Sarajevo for four years is something I would never wish happen again. Never on the worst enemy. It’s a prime instance of what war can do. It destroys life and destroys faith in goodness and fairness. You need a lot of strength to overcome what happened and to move on. Everyone who has been through something like that, and survived it, is in some way a hero. You don’t have to be a soldier; you can be just a kid.

In talking with some other artists, including Damir Imamović, it was explained to me that it took the war to revive the interest in sevdah music. Prior to the war, it was primarily older people who were attracted to the genre, not the youth. The war changed all that. Is this a correct interpretation?

It’s very individual, you know, how you see it. I was a kid when I listened to sevdah. So my experience defeats that thesis. In the majority of cases, that was probably true; I was one of the few that age to listen to that kind of music. It wasn’t that popular, although it was on the radio non-stop and on the television. The seventies were the golden age of sevdalinka. During the war and after the war people started going back to their roots and discovering who they were. We lost the country overnight. So, for some people that could have been the reason that they turned to this kind of music.

But with you it was different. You had a sense of continuity which extended to before the war.

Absolutely.

Sarajevo is a city between East and West. Where are your affinities? More with the Orient or more with the Occident? Or a mix of both?

That’s what I said. I am very lucky that I was in Sarajevo, because it is a very special place in very many ways. It’s a crossroad of very many cultures. I feel I belong to all of them by nature of having lived in the city. And that is beautiful.

At some point you said that you “hated the accordion,” a statement which seems to me strange because the accordion plays such an important role in traditional Bosnian music as well as sevdalinkas.

“Hate” is too strong a word. I just wasn’t a fan of certain arrangements where the accordion is overplayed. It covers up everything else. It’s a beautiful instrument, but in many cases it’s just misused; it’s not used in a proper way. This is just my view. But then I have heard how the modern classical accordion sounds, and it’s like a totally different instrument. I fell in love with it. In the end now in the band I do have an accordionist. But we do try to make arrangements so that the instruments are all submissive to the lyrics and the story, instead of showing everyone up, as if to say “look how wonderful I can play this accordion,” and overshadowing everything else. I think it is just a matter of measure, not to overuse it. Merima Ključo, the accordionist with whom I made the album Zumra – she studied modern classical accordion in Rotterdam, we met and I said to myself, “this is not the accordion that I know.” It was introduced to me in a different way.

What about narodna muzika – so-called “folk” music? Is it possible to say something positive about it?

There is some brilliant music coming from that direction. Some people, when they say narodna muzika – “folk” music – they give it a negative connotation. It’s unfair, because there are so many brilliant songs coming from there. Like Toma Zdravković and Silvana Armenulić, who I actually dedicated my latest album to; to the songs that he wrote for her, and are beautiful, beautiful songs. Not like traditional music, but folk music. But we could discuss that for quite some time: Is sevdah folk music? For many of the sevdalinkas you don’t know who the author is, yet they came from the people. This kind of narodna muzika, with the arrangements – there are some beautiful examples, seriously, and there are horrible ones as well, to be sure.

What do you think about Halid Bešlić?

I know him personally. He’s a really good man. That’s the first thing. A really good person. His music is like that, like what you were taking about: narodna muzika – popular folk music. He’s sort of an icon.

The Bosnian Frank Sinatra.

Yeah. No party is complete without one of his songs. Although I am not someone who is listening to those songs. But I know of them and they stay with you. They are very catchy songs.

Dropping some more names: Damir Imamović, who we mentioned earlier?

I love him. He just recently, three or four years ago, wrote me a song, the lyrics and the music, and I fell in love with it. He’s a fantastic composer and songwriter. We are good friends. You know he’s got this “Sevdah Lab”. He talks about the history of sevdah. He knows quite a lot. He digs into archives and researches all the songs: where do they come from? Who wrote them? He’s doing a really great job. I really like him.

Just throwing some stuff at you: between 2003 and say 2012 there was this Balkan Beats hype. What do you make of that?

Like Shantel.

Right.You were never really part of that. You, rather, kept aloof from it. What do you think of it as a fad?

Well, I’m glad that sevdah lives. In whatever form it expresses itself in. It doesn’t matter. You can’t destroy its core, its origin, its power. Many people used the folk elements – the sevdah elements – in their new songs, in their new creations. And many DJs made use of sevdah in their songs, and it’s brilliant; I like it. I am very much supportive of that. As long as it stays nice and doesn’t get too over-the-top.

What about the future? Do you still see there being enough space to express yourself by means of traditional song in Bosnia and the Balkans?

In general I am very glad, actually, that you and I are sitting here, talking about sevdah; that is amazing for me, in and of itself. Because some years ago many people didn’t even know that it existed. The fact that it is there and that it is being presented to the rest of the world is very rewarding for me. And that is actually, one of the main reasons I am doing this, what I am doing now. There are brilliant musicians living here among us, and every once in a while I hear about someone new coming up, and I always support the youngsters in their desire to create, not necessarily sevdah-based songs – it’s very hard, you know, because this country has many problems. There is no music industry, though I am not fond of that word. There is no structure or good foundation to help the emerging artists. So, it’s all very individual attempts, and the up-and-comers need all the support that they can get. So I think that this country has a lot more to give in terms of music. And it’s happening, and it’s brilliant. I know some young musicians who are in the studio, right now as we speak. There’s one girl – Esma – she’s brilliant, and she writes her own songs. I wish that Sarajevo comes back to the musical glory that we used to have.

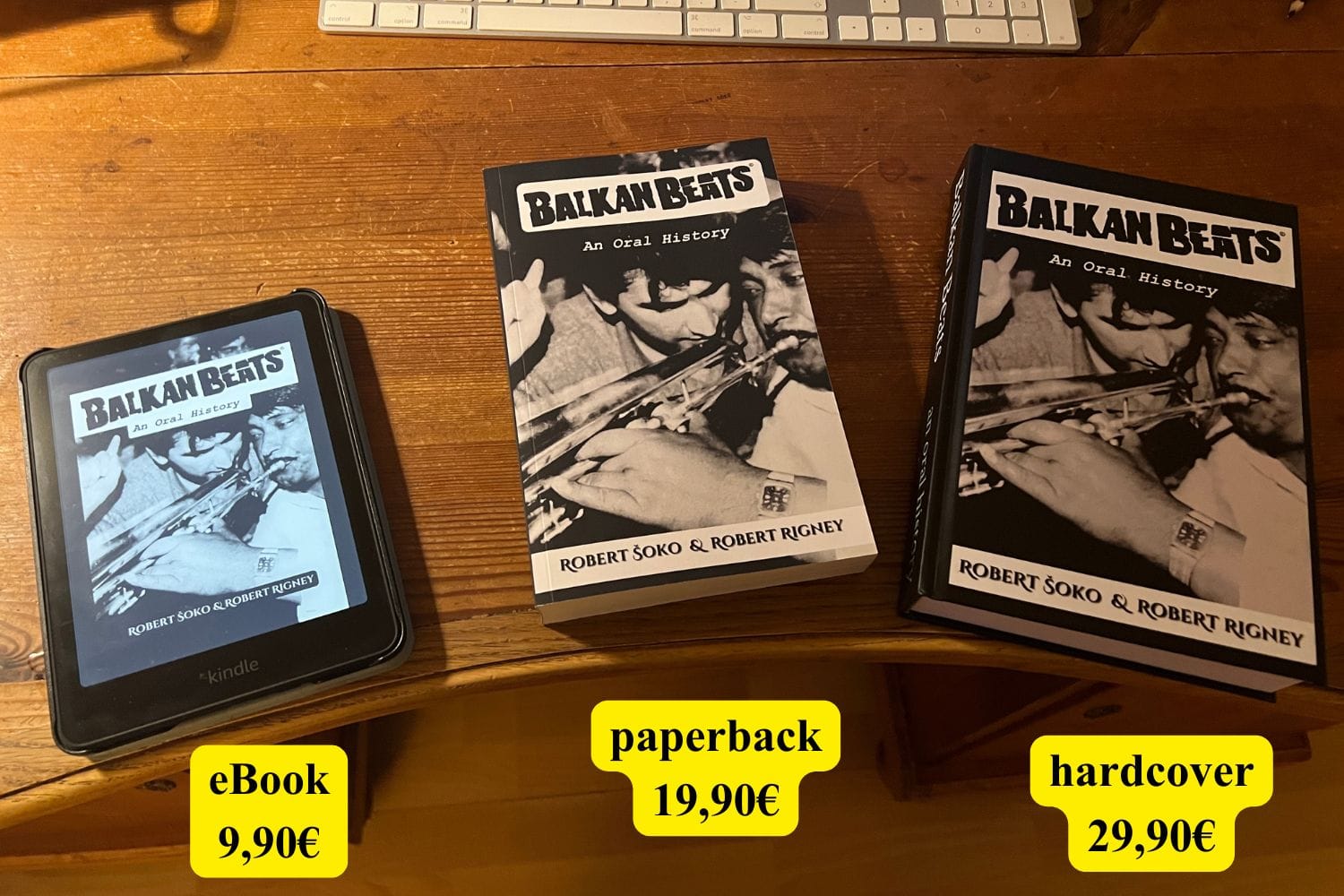

+++ This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book +++

Amira Medunjanin (Dedić;[1] born 23 April 1972) is a Bosnian singer and interpreter of sevdalinka. She holds both citizenship of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Medunjanin was born in Sarajevo and her fascination with the Music of Bosnia and Herzegovina led her to devote herself to creating a unique voice within sevdalinka.[2]

Singer, humanitarian, and global ambassador for both the culture and music of her native Bosnia and Herzegovina and the wider Balkan region.

Source Wikipedia

“I never thought about adopting music as a profession.”

an Interview with Amira Medunjanin

by Robert Rigney Berlin 2024

How did it come about that your English is so perfect?

I don’t know. I picked it up over the years. I worked for the British military service in Croatia. And before that, I worked for UNPROFOR, and then I worked for the European Commission for twelve years. So basically, it was the official language.

You speak with a very distinct British accent.

Yes, it’s because I worked with them for quite some time. I picked it up. That’s what people say about singers; They pick up the accents very easily. Because I have spent most of my time with Brits, you know. Yeah, so it’s stuck with me.

Where are you located at the moment?

I am in Sarajevo at the moment. Actually, I am between two countries. I live in Croatia and in Bosnia. I live in a small city in Istria, on the coast. But since this pandemic has started, I have been spending more time with my parents here. So it’s sort of like I am being torn between two words. But I was born in Sarajevo. I come from here.

What was it like growing up in Sarajevo?

It’s a typical small part of Sarajevo, where all of the houses are so close they are almost attached to each other. We call it mahalle. Growing up in Sarajevo was very special in so many ways. It’s a special place. It’s a special city. Nowadays it is very different to what it used to be when I was a kid. Still, some of the old remain, especially in the old part of town. When I say, mahalle, I mean everyone knows everyone. If you want to have a coffee with a neighbor, you don’t have to call in advance. They just pop in the door.

It’s still that way.

In my neighborhood it is. Not many people who were born in Sarajevo remained here, unfortunately. But you can still find the old way, and that’s what I like about it. It’s very open and very free. You walk down the pavement of your block, you can smell the different kinds of cuisine coming from the open windows. I like that closeness. When I think of my childhood I recall the smells, among other things. And of course, the music coming from all of the houses. It was always like that: open doors and open windows when the weather is nice and sunny spilling music. I have more memories of the sunny days than the winter.

Amira is a Muslim name. Do you define yourself as such?

I’m a Bosnian. Born in Sarajevo. But yeah, my name is Muslim. I come from a Muslim family. But you see, when it comes to the feeling where you belong to, I always say that I am a Bosnian. And Sarajevo is in Bosnia. So I am always a Bosnian and a Herzegovinian, whatever that is.

What was Sarajevo like in terms of music before the war?

Sarajevo was a Mecca musically. Many fantastic bands come from this city and musicians in general. Not just bands, but individual singers. It was like a cradle of music. Many people said that if you could win over the audience in Sarajevo, you could make it anywhere. Sarajevo was really very strong when it came to the music scene. Seventies, eighties – that was the time. Especially when the New Wave started. Everyone was pushing to achieve his or her place in the music scene. It was so rich and beautiful. All sorts of different bands were emerging. It was a different time than today. We all grew up on very good music. I’m pretty lucky to be able to say that.

What were you listening to back then specifically?

Well, besides sevdah, which is really a part of my culture, part of my nature and part of me, I listened to all sorts of music. As a teenager I was really into punk, and I still am. Maybe my hair proves that. I was totally crazy about – I have said this so many times – but I really loved Nick Cave and his writing. Especially his poems and his way of bringing music to people. He’s not bound to any trend. He goes his own way, and I really admire him for that. Aside from that, local bands, like Ekaterina Velika from Belgrade and Azra from Zagreb, Leb i Sol, a brilliant band from Macedonia. I listened to all that kind of music. The Beatles were something you had to know. I was encouraged to know everything about the Beatles. So when it comes to the music that was shaping me through my childhood and the later years, it was coming from everywhere. I sometimes reach for classical music as well; it’s very relaxing. But I can say that I am the child of New Wave.

Did you ever listen to Bijelo Dugme?

Oh, yeah. I sing some of their songs on my concerts. I find this stuff interesting, although they say I am a sevdah singer. So, I prefer not to be labeled that.

What sort of musical environment did you grow up in at home?

It was more sevdah. My mom is totally in love with that music. She was actually the one who helped me understand the songs. I would sing as a child and she would correct me if I was wrong in certain parts. She was my first audience. At home we were really listening a lot to sevdah. Especially on the radio. It was very popular. I still listen to radio a lot. It’s my preferred media.

Do they play a lot of traditional stuff on Bosnian radio stations?

Yeah, there are various radio stations. Back in the old days, in the eighties, Radio Sarajevo was a good radio station. They were also organizing a lot of auditions for emerging singers, especially sevdah singers. It was a quite lovely educational climate, growing up in Sarajevo.

Did you have any ambitions to be a singer prior to the war?

I didn’t really. If I had any ambitions, I would have gone to music school. I don’t read music. I can’t read scores and stuff like that. So I am basically a self-taught musician. I never thought about adopting music as a profession. Because music is something – I don’t know quite how to put it – sacred in a way. I don’t see myself as a professional nowadays, although I live off of music and make a living from singing. I’m just fortunate to do something that is precious, not just for me, but for so many people. And then to be able to live off of that, is truly a blessing. You know what I mean? But no, as a kid, and in my younger days, I never had any aspirations. I studied something completely different: economics.

How did you experience the war and the siege of Sarajevo?

I can tell you that I almost never, ever talk about it. I was here, and I survived and that’s it. It was something that I wouldn’t wish upon anyone. It’s not that I don’t like talking about it. It’s just that I am trying to – not to forget (you can’t forget it). You know, it’s very strange. A lot of people ask me about it. I don’t even know how it was or how we survived. I have no idea how I survived. Out of pure luck, I suppose.

You can identify with what is going on now in Ukraine, I’d imagine; the images must hit home.

In general, I despise the very idea of violence. What we went through in Sarajevo for four years is something I would never wish happen again. Never on the worst enemy. It’s a prime instance of what war can do. It destroys life and destroys faith in goodness and fairness. You need a lot of strength to overcome what happened and to move on. Everyone who has been through something like that, and survived it, is in some way a hero. You don’t have to be a soldier; you can be just a kid.

In talking with some other artists, including Damir Imamović, it was explained to me that it took the war to revive the interest in sevdah music. Prior to the war, it was primarily older people who were attracted to the genre, not the youth. The war changed all that. Is this a correct interpretation?

It’s very individual, you know, how you see it. I was a kid when I listened to sevdah. So my experience defeats that thesis. In the majority of cases, that was probably true; I was one of the few that age to listen to that kind of music. It wasn’t that popular, although it was on the radio non-stop and on the television. The seventies were the golden age of sevdalinka. During the war and after the war people started going back to their roots and discovering who they were. We lost the country overnight. So, for some people that could have been the reason that they turned to this kind of music.

But with you it was different. You had a sense of continuity which extended to before the war.

Absolutely.

Sarajevo is a city between East and West. Where are your affinities? More with the Orient or more with the Occident? Or a mix of both?

That’s what I said. I am very lucky that I was in Sarajevo, because it is a very special place in very many ways. It’s a crossroad of very many cultures. I feel I belong to all of them by nature of having lived in the city. And that is beautiful.

At some point you said that you “hated the accordion,” a statement which seems to me strange because the accordion plays such an important role in traditional Bosnian music as well as sevdalinkas.

“Hate” is too strong a word. I just wasn’t a fan of certain arrangements where the accordion is overplayed. It covers up everything else. It’s a beautiful instrument, but in many cases it’s just misused; it’s not used in a proper way. This is just my view. But then I have heard how the modern classical accordion sounds, and it’s like a totally different instrument. I fell in love with it. In the end now in the band I do have an accordionist. But we do try to make arrangements so that the instruments are all submissive to the lyrics and the story, instead of showing everyone up, as if to say “look how wonderful I can play this accordion,” and overshadowing everything else. I think it is just a matter of measure, not to overuse it. Merima Ključo, the accordionist with whom I made the album Zumra – she studied modern classical accordion in Rotterdam, we met and I said to myself, “this is not the accordion that I know.” It was introduced to me in a different way.

What about narodna muzika – so-called “folk” music? Is it possible to say something positive about it?

There is some brilliant music coming from that direction. Some people, when they say narodna muzika – “folk” music – they give it a negative connotation. It’s unfair, because there are so many brilliant songs coming from there. Like Toma Zdravković and Silvana Armenulić, who I actually dedicated my latest album to; to the songs that he wrote for her, and are beautiful, beautiful songs. Not like traditional music, but folk music. But we could discuss that for quite some time: Is sevdah folk music? For many of the sevdalinkas you don’t know who the author is, yet they came from the people. This kind of narodna muzika, with the arrangements – there are some beautiful examples, seriously, and there are horrible ones as well, to be sure.

What do you think about Halid Bešlić?

I know him personally. He’s a really good man. That’s the first thing. A really good person. His music is like that, like what you were taking about: narodna muzika – popular folk music. He’s sort of an icon.

The Bosnian Frank Sinatra.

Yeah. No party is complete without one of his songs. Although I am not someone who is listening to those songs. But I know of them and they stay with you. They are very catchy songs.

Dropping some more names: Damir Imamović, who we mentioned earlier?

I love him. He just recently, three or four years ago, wrote me a song, the lyrics and the music, and I fell in love with it. He’s a fantastic composer and songwriter. We are good friends. You know he’s got this “Sevdah Lab”. He talks about the history of sevdah. He knows quite a lot. He digs into archives and researches all the songs: where do they come from? Who wrote them? He’s doing a really great job. I really like him.

Just throwing some stuff at you: between 2003 and say 2012 there was this Balkan Beats hype. What do you make of that?

Like Shantel.

Right.You were never really part of that. You, rather, kept aloof from it. What do you think of it as a fad?

Well, I’m glad that sevdah lives. In whatever form it expresses itself in. It doesn’t matter. You can’t destroy its core, its origin, its power. Many people used the folk elements – the sevdah elements – in their new songs, in their new creations. And many DJs made use of sevdah in their songs, and it’s brilliant; I like it. I am very much supportive of that. As long as it stays nice and doesn’t get too over-the-top.

What about the future? Do you still see there being enough space to express yourself by means of traditional song in Bosnia and the Balkans?

In general I am very glad, actually, that you and I are sitting here, talking about sevdah; that is amazing for me, in and of itself. Because some years ago many people didn’t even know that it existed. The fact that it is there and that it is being presented to the rest of the world is very rewarding for me. And that is actually, one of the main reasons I am doing this, what I am doing now. There are brilliant musicians living here among us, and every once in a while I hear about someone new coming up, and I always support the youngsters in their desire to create, not necessarily sevdah-based songs – it’s very hard, you know, because this country has many problems. There is no music industry, though I am not fond of that word. There is no structure or good foundation to help the emerging artists. So, it’s all very individual attempts, and the up-and-comers need all the support that they can get. So I think that this country has a lot more to give in terms of music. And it’s happening, and it’s brilliant. I know some young musicians who are in the studio, right now as we speak. There’s one girl – Esma – she’s brilliant, and she writes her own songs. I wish that Sarajevo comes back to the musical glory that we used to have.

+++ This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book +++