Interview with Aleksandar Hemon

By R. Rigney and R. Šoko, January 2025

Robert Rigney: I’m here with the DJ Robert Soko.

Robert Soko: Dje si jarane.

Aleksandar Hemon: Pozdrav.

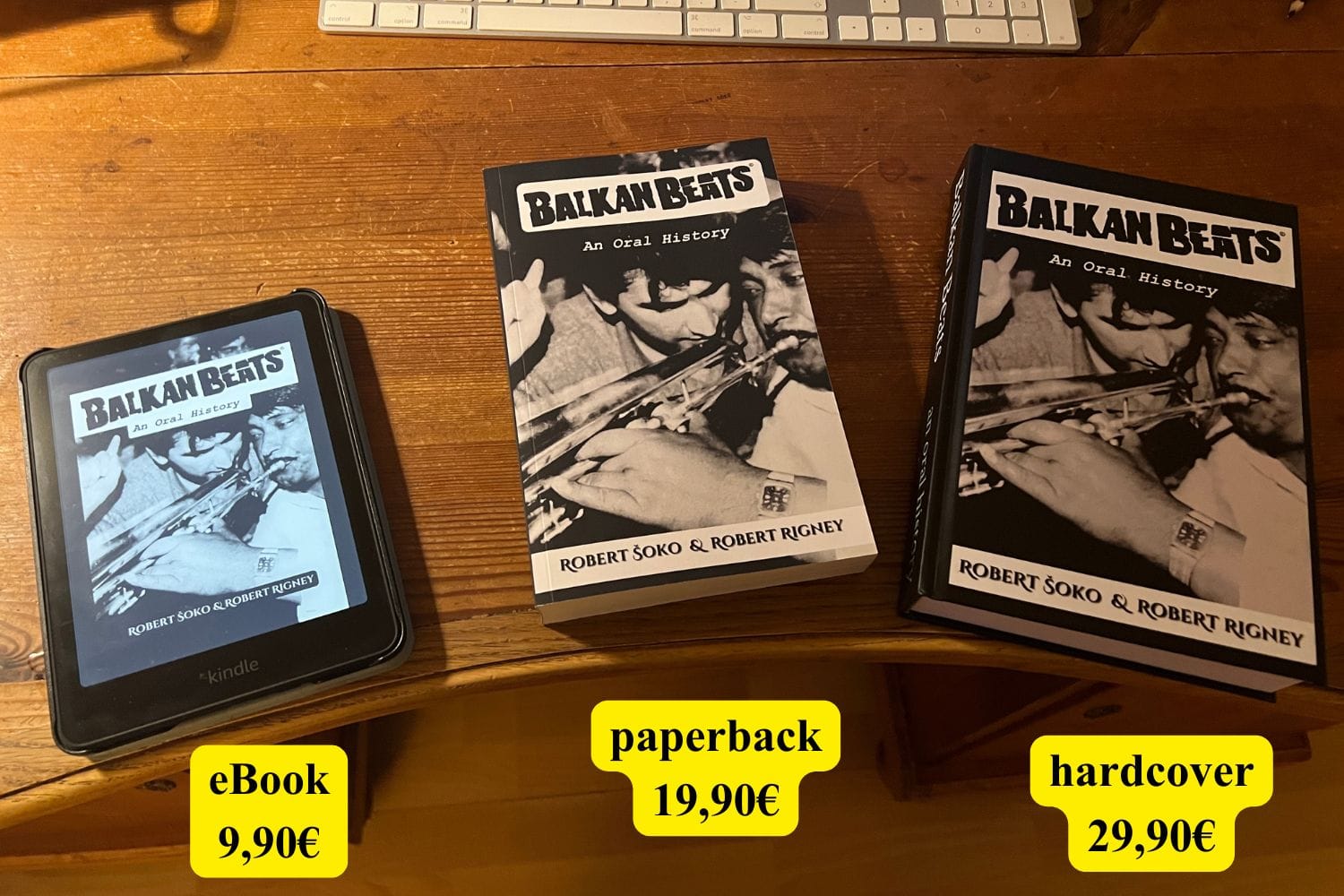

Robert Rigney: We are working on a book at the moment. The tentative title is, Balkan Beats Book. We have a ton of names, talking about music, but not only music. We have some actors, photographers, artists…people not directly related to the Balkan Beats scene. To have you on board is a great honor. Maybe we can begin with talking about Sarajevo. You left before the war, I take it.

Aleksandar Hemon: I left in January of 1992. So, a couple of months before the war. The war in Bosnia. The war in Croatia was ongoing.

Robert Rigney: What part of Sarajevo did you grow up in?

Aleksandar Hemon: It used to be called Stara Stance. The Old Train station. The Austro-Hungarian train station built in the 1870s. But you have to be of my generation or older to remember that there was a neighborhood. The tram stop is Socialno. Socialno means “Social Security”. It was across the river from the football stadium. Robert would probably know.

Robert Soko: I’m from Zenica, basically. But of course, I know Sarajevo as well.

Robert Rigney: We have spoken to various people like, Goran Bregović, Dr. Nele Krajalić, Srđan Gino Jevđević, for instance, about the heady climate that was Sarajevo at the end of the eighties. There was a lot going on in terms of culture. What was your impression of Sarajevo? Was it a provincial backwater, or was it a place where a lot of things were happening culturally?

Aleksandar Hemon: It was not a backwater. I thought it was the most interesting place in Yugoslavia at the time. The other cities were pretty good. Good things were happening there. It was this period in Yugoslavia between Tito’s death and the beginning of the war where there was a general liberalization and also people coming of age, like my generation, which meant music, movies, books, radio, press. It all came together. Bregović belonged to the time before that. He kind of tagged along. But he was not at the forefront of anything, ever. I detested him, and I have detested him since I was a teenager.

In any case, there was this window in between communism and fascism, where it seemed possible – everything seemed possible – including politically, to create some kind of different social order, bordering socialism. We felt that with culture and music we could win the battle. But they had the army and the police and the institutions, and the money and a history of fascist ideas in certain parts, and all that. So, we lost the battle.

But at the time it was very exciting. In many ways we were at the forefront. We had been neglected because of Bosnia’s complex political structure and there was a tighter control over Bosnian Sarajevo. And once it was loosened there was this potential that came up. And I loved it. Obviously, I love Bosnia and Sarajevo. It has never been mono-ethnic. It was always multicultural, multilingual.

It is also importantly, I think – and not completely positively – but it was rapidly urbanized after WWII. It was a backwater, and then it wasn’t. Because it was industrialized. There were these state companies that were doing very well, which allowed the middle class to rise. I’m a product of the middle class. But the houses had dirt floors. So that the kids had ideas. And it all came together at the same time. Even Krajalić, who is a fascist now, but he was a part of that. And Bregović, who was just trying to tag along with his instinct. But it was amazing. And then little by little, as with everything it Yugoslavia, it started coming apart.

Robert Rigney: And your leaving Bosnia was a direct result of the war?

Aleksandar Hemon: I was invited another time to go to the States for a month, organized by the United States Information Agency. They used to have cultural centers all over the world. The Republicans shot that down. But back in the day there was an American cultural center in Sarajevo and in Belgrade and Zagreb and in other places. They would invite people from all over the world to come on a trip to the United States for a month to facilitate cultural exchanges. Cultural engineers would be invited, too. It was scientific, too. So I came along with that for a month. I was a young journalist in the eighties. And I went around the United States. And after that I stayed on to see some friends in Chicago. That was my last stop. I was supposed to go back to Sarajevo May 1 in 1992. And May 2 the siege completely closed it down. By that time I had decided to stay in Chicago.

Robert Rigney: How was that for you when the war broke out, you being in America, presumably watching the news, anxious about friends and family?

Aleksandar Hemon: All that. There was no internet. So I was watching CNN which was broadcasting the same story seventy times a day. Rumors were coursing about. There was internet technically. But it was not available to the populous. So there was no way to be in touch. I wasn’t planning to stay. I had no money and no clothes, no immigration status. So eventually I had to find a job, a low-wage job, for Greenpeace; I was a canvasser. Eventually I started writing in English.

Robert Rigney: This comes forth in your novel, Nowhere Man. Also in the novel there is this incident where a guy from ex-Yugoslavia – a Bosnian Serb, and a nationalist – makes the protagonist an overture of friendship, which is rebuffed. How was it for you when in the States, you met people from Bosnia – Muslims, Serbs, Croats – did you instinctively embrace these people, or were you rather more stand-offish?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, in my mind, ethnicity is not that important. Ethnicity does not result in a political position. If your call yourself a Bosnian, it has nothing to do with ethnicity; it is a matter of citizenship. It’s like calling yourself an American. It implies a sense of ethics and politics. I’m of, what is called, “a mixed heritage”. Whatever that means. I hate that term. “Mixed marriage,” even. My father is from a Ukrainian speaking family. But he and all of his siblings were born in Bosnia. My grandparents from my father’s side were born in today’s Ukraine. They came to Bosnia at the time of the Austro-Hungarian empire. My mother calls herself to this day a Yugoslav and a Bosnian. And they always lived on this side of the river Drina. The other side is Serbia. They were progressive. My oldest uncle was in the Partisans. My mother has always been a communist. I’m a leftist progressive. So, I have always been Bosnian and Yugoslav. Actually, when it all fell apart I was calling myself a Ukrainian to increase the number of Ukrainians in Bosnia. There were only five.

The point is, though, if people declared themselves as Bosnian, I would hang out with them. They could be a Bosnian Serb or Bosnian Croat or whatever. In Chicago there was a lot of immigration stemming from WWII and the fascists. In some neighborhoods you could tell from signs and flags who was who. I tried to stay away from all that.

In the mid-nineties when the war started, the Bosnian refugees started coming to the United States and a lot of them came to Chicago. A lot of them came to the neighborhood where I was living, Edgewater. The rent was cheap. I looked out the window one day and I saw a Bosnian family walking down the street. It was the typical Bosnian family formation: the man at the front and in the wings the sons and the woman behind. It was like a flock of Bosnians. I saw them through the window and I instantly knew they were Bosnians. There was just the formation to go on; there were no other signs.

So they all landed in my neighborhood and elsewhere in Chicago, including some of the people I had known from before. I started hanging out with them and doing different thngs with them. Those were refugees, people who had been in concentration camps, who were, as the euphemism goes, “ethnically cleansed”. They were traumatized much more and much differently than I was. I had a job and I knew the language and all that. So I didn’t spend my days in these circles. But I would meet them and exchange words with them and was hanging out with them.

Robert Rigney: In talking to Srđan Gino Jevđević of Seattle ethno-punk band Kulturshock, he described the woeful ignorance of a lot of Americans with regards to the geography of East Europe, specifically ex-Yugoslavia. Did you find that a lot of Americans were misinformed about the basic facts of ex-Yugoslavia?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, it depended on who you talked to. The conflict was on the front pages. And American people read newspapers. Not just Twitter. So, it was on the front pages and in the news all the time. It was the biggest war in Europe since WWII. However, people didn’t know the details. They didn’t know exactly where Yugoslavia was, or where Bosnia was. They knew it was out there somewhere. I didn’t often encounter total ignorance. More confusion.

When I was canvassing people would ask me where I was from. Some people would know, and they would know a lot. Some people confused Yugoslavia with Slovakia. I once – because I was speaking English, obviously – a Serb guy invited me in and unfolded a map of Serbia from the fifteenth century and explained to me why the Serb position was the right position, and that there was a world-wide conspiracy against the Serbs going round.

Robert Rigney: This guy pops up in Nowhere Man.

Aleksandar Hemon: Exactly. And I would go out and go to parties and people would ask me where I was from. I would say, “Bosnia”. And they would ask me to “explain it simply,” what was happening. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to party and get laid or whatever. Eventually, I would say that I was Ukrainian. A few times – as in Nowhere Man – this I remember, I said was from Luxemburg, because everyone had heard of it, but no one knew where it was. Probably the president doesn’t know where it is. Trump doesn’t know where it is, and will never know. So, it got to the point that I didn’t want to explain anymore.

Robert Rigney: Let’s talk about music because time is short. Music has probably played a role in your life since your teenage years in Bosnia. I’m sure you came across – and Brega is the best example – this “Balkan Beats” phenomenon, putting beats to folk music. What’s been your take on this stylistic direction?

Aleksandar Hemon: There is turbo-folk, which is folk to beats. That was the music of war, though it is a simplification. It’s not the beats. It’s using electronic instruments to make music, which makes it cheaper and you don’t need an extensive studio or a genius accordion player, which was what you needed in the old way, the sevdah way. In Socialism, the state institutions, as their duty, saw to it that people’s heritage was preserved. So the ethnographers and ethnomusicologists would record their catalogue in various versions. Damir, as you well know, his father and his grandfather were involved in that. A canon was established of Bosnian recordings. There were some recordings by ethnomusicologists earlier, but much of that was recorded in Socialism. It required an orchestra and all of that sort of infrastructure. And because I was a punk kid, I thought, “Eh, all of that is shit! I don’t care about these peasants!” And then it became worse, because now I love it. But turbo-folk kind of simplified all of that. It was folk music that was a derivation of traditional music, which I detested.

But I was DJing with someone who was much younger than me, whose genre was break-beats. She started mixing in Seka Aleksić, and the kids went crazy. While I appreciate, intellectually what they were doing, I have no tolerance for stuff like that.

Balkan Beat can mean a lot of things. When I was young we would tell this story about how a Paris symphony going to perform a traditional piece of Macedonian music, but their percussionist fell ill and they couldn’t find anyone who could play in his style and then they found this Macedonian nigger, who said, “Yeah, I’ll do it.”

In the eighties, in Yugoslav pop music there was this hybrid transformative influx of traditional beats. Like bands like Haustor and Idoli. Also the eighties was the time of so-called World Music. Talking Heads and Paul Simon. So there was this traditional influence in Yugoslav pop and rock music. But it was used differently. It wasn’t just looping, or sampling. It was integrated. We all liked it. So there was a different sort of interest in traditional idioms. And it became cool.

Robert Rigney: Did your coming round to traditional Balkan music coincide with your discovering Damir Imamović?

Aleksandar Hemon: It pre-existed that. Some of the songs everyone knew. You would get drunk at a party and you were in a certain state of mind, you would sing them. They also recorded these songs, and you could hear them on the radio, and so on. And that was reacted during the war, right?

It was in reaction to the war, right? Sevdah. It became important to us suddenly, us realizing that this is valuable, which they were trying to destroy. It was just out there, and you were thinking it would last forever. And you said, “I’d rather listen to punk.” They set out to destroy all that. And then you would get to thinking, but I don’t want to stand by and let that happen. There was a whole new generation. Damir. Amira. They were young, cool kids. They listened to rock and pop music, but thought: “I can do this.”

Mostar Sevdah Reunion was the breakout point. They did it in a way that is cool. It wasn’t the official radio orchestra with an accordion…and the orchestra there, sitting in suits, in a studio, playing this. It became valuable and cool. They revived it.

And then Damir carried it further and further. What Damir has done is discover the “queer notes” in sevdah. So, reinterpreting – not reinterpreting – but opening up that space. What we didn’t like about sevdah was that it was traditional. We were young kids interested in social and cultural change. Everything traditional was suspect. Not only my parents’ stuff, but my grand parents’. I loved them all, but after the war. It assumed a different value, before the war and after the war. The kids took to it.

Robert Rigney: The thing about a lot of sevdah music is that it had a lot to do with star-crossed lovers who were stymied by a conservative society, prevented from living out their love for each other. Today, in an atmosphere of instant gratification, the songs seem antiquated and foreign. But for queers in Bosnia it may be different. Society is still constructed so that such same-sex relationships are frowned upon. So that in the hands of one of them – of a Damir or Bozo Vreco – a sevdah song, given its new queer subtext, takes on – or still has – an added relevance.

Aleksandar Hemon: Robert (Soko), you probably know this song, this very famous Bosnian song, “Snijeg pada na behar, na voće.” It’s a very traditional song. It’s one of the classic sevdah songs. My parents sang it. Everyone has song it. It’s an unofficial anthem of the queer pop movement of Bosnia. At the first Pride in Sarajevo, Damir sang this song.

Robert Soko: I had no idea. There was also Himzo Polovina, who was gay.

Aleksandar Hemon: It was always very encoded. I knew his son. But yes, it was always there. It was this sort of unrequited desire among queer people but also amongst women. Arranged marriages crossed all ethnic lines. There was a lot of prohibition, a lot of control of love and desire. Sevdah was a way out of it. Some queer people can therefore identify with these songs. The way Mostar Sevdah, Amira and Damir open up these things. People lose their minds in these songs because they can’t see the neck of a girl.

With regards to Damir and my collaboration – I had already known him from the past – but it was I who approached him. It turned out wee had a lot of common friends. I loved his music. The difference with the new generation was not that they were trying to preserve it.

The old way – as it was presented on radio and television – was to preserve the songs. They were not, of course, preserving it, rather they were modernizing it. The accordion was not a traditional sevdah instrument, and so on. But, officially they were preserving it. All the while, they were updating it.

Damir has done amazing work in that regard.

So when I was writing my book, The World and All That It Holds, which is about queer love between two Bosnians, it occurred to me, insofar as they sing songs to each other – sevdah songs, but also Sephardic songs – which really overlap – and the unofficial song of Sarjevo is “Kad Ja Podjoh Na Bembasu” is a Sephardic song. Sephardic music. But the words ae local. Anyway, they were singing songs in the novel. And my idea was, “What if Damir recorded some of those songs?”

So, I contacted him and proposed it to him half way through my first draught. He liked the idea. He started writing and recording some songs. He found some older versions of Sephardic songs – and also Bosnian songs – and reinterpreted them in his own way. He would send me demos. I would send him chapters. He would write a song, “Bejturan”, for instance, the lyrics written by a Bosnian refugee in Sweden.

Then I reintegrated those words, anachronistically into the novel. And he wrote a book about Osman, which is the name of one of the characters.

Because Folkways Smithsonian was trying to do something with him, I pitched this to them as an album. And we were trying to coordinate the album and the book, having to do with organizing a tour in the United States.

Robert Rigney: Did anything come of those plans?

Aleksandar Hemon: No. It wasn’t coordinated between my publisher and his publisher. But he might still come.

Robert Rigney: Speaking of The World and All That It Holds, to tell the truth, I am not a big fan of historical novels. I appreciate, rather, writing that is direct, unmediated, relating to things I have experienced in my life. But you wrote an historical novel, and I wanted to know, what is the trick in writing an historical novel?

Aleksandar Hemon: The material has to be modernized in some way. I can not compare my methods to some other -so-called – novel writers methods, just because I don’t know where they are. But one thing is that I ensure that the narrator is present in this time. It’s a particular point of view. It is not projected. It does not come from the position of historical authority, historian authority. Rather it is from the point of view of someone who is trying to figure it all out. Because for us in the Balkans history is continuous. To me there is a continuity there. So, whatever is in the book, it is continuous with this time. It’s not something that happened in the past that has no connection with this. Costumed people and so forth. That’s not what it’s all about.

Robert Rigney: In The World and All That It Holds, one of the main characters is Jewish. You have used other Jewish protagonists in your writing, though you yourself are not Jewish. What is it about the figure of a Jewish protagonist that resonates to you?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, in this particular book, he is Bosnian, and a part of the Bosnian landscape. And Pinto, my character, had been there since the 16th century. In Sarajevo. So, he’s not just Jewish, just like Osman is not just Muslim. There are layers of identity.

Having said that, the central fact of my life is displacement. No people have more stories of displacement than Jewish people. In many ways theirs is the template for displacement narratives. It starts in the fucking bible.

In this book, specifically, it all started with music, essentially. In the great eighties someone gave me a cassette tape called Memories of Sarajevo by a woman called Flora Jagoda. Flora Jagoda left Sarajevo in 1947 as a young Jewish woman, who had survived the Holocaust and ended up in Baltimore, and who sung songs of Sarajevo about Sephardic Jews to her children and grandchildren.

Eventually, in 1989 she was talked into recording those songs as an album. She recorded two albums, Memories of Sarajevo, which came to be known as Songs of my Grandmother. And she died a couple of years ago at the age of 96. Before the war I got hold of this recording, and I loved it so much because she sang in Ladino. But a lot of it was very much related to what I knew from Sarajevo; to sevdah. The harmonies, the scales. The way she pronounced certain sounds like people in Sarajevo pronounced them. To me, I just flipped. So, I imagned writing this book. These are some of the songs that Pinto sings to Osman. And I started being interest in the Jewish, Sephardic history of Sarajevo. And the fact that it was all wiped out. I know the old Jewish neighborhood, where the synagogue was, though it is barely marked.

And Socialism had it that the people who were killed were “the victims of fascism. There was no differentiation. It was one of the clumsy ways to cover up the inter-ethnic conflict that took place during WWII. There is a monument to the victims of fascism above Sarajevo. You have these walls and stones laid out like steps, the walls with the names of the victims. You have whole walls with the names of Jewish victims. “Victims of Fascism”. So their extermination was not owing to the Holocaust; it was “fascism”. They did it in the Soviet Union, too. That was the kind of narrative during Socialism. So, as a writer I wanted to recover that forgotten history. So that Jewish history was interesting for me insofar as it was also the history of Sarajevo.

Robert Šoko: The World and all that it Holds completely blew me away. I was curious about the feedback. Because the book was such a masterpiece that I asked myself would people in the Balkans get the message and what impact would it have on this culture here which is still being poisoned by a lot of prejudices and nationalisms.

Aleksandar Hemon: People in Bosnia and the region love me and I love them. But it’s also a self-selecting audience. Fascists don’t read me, let’s put it like that. They probably don’t know about me, because I don’t move in those circles. The people what do know me are people who think of Bosnia as the land of possibilities that was fucked up and who revel in the complexity of the place, which is what I love. That complexity came at a high price. There was a war and fascists tried to destroy it and still are trying to this day. But people who read my books identify with that idea: the complexity of Bosnia.

+++ This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book +++

Aleksandar Hemon (born in Sarajevo, Bosnia, September 9, 1964) is a Bosnian–American author, essayist, critic, television writer, and screenwriter. He is best known for the novels Nowhere Man (2002) and The Lazarus Project (2008), The World and All that it holds (2023) and his scriptwriting as a co-writer of The Matrix Resurrections (2021).

Hemon is also a musician, distributing his Electronica work under the pseudonym “Cielo Hemon.”

“The central fact of my life is displacement.”

an Interview with Aleksandar Hemon

by Robert Rigney & Robert Šoko, January Berlin 2025

An Interview with Aleksandar Hemon

Robert Rigney: I’m here with the DJ Robert Soko.

Robert Soko: Dje si jarane.

Aleksandar Hemon: Pozdrav.

Robert Rigney: We are working on a book at the moment. The tentative title is, Balkan Beats Book. We have a ton of names, talking about music, but not only music. We have some actors, photographers, artists…people not directly related to the Balkan Beats scene. To have you on board is a great honor. Maybe we can begin with talking about Sarajevo. You left before the war, I take it.

Aleksandar Hemon: I left in January of 1992. So, a couple of months before the war. The war in Bosnia. The war in Croatia was ongoing.

Robert Rigney: What part of Sarajevo did you grow up in?

Aleksandar Hemon: It used to be called Stara Stance. The Old Train station. The Austro-Hungarian train station built in the 1870s. But you have to be of my generation or older to remember that there was a neighborhood. The tram stop is Socialno. Socialno means “Social Security”. It was across the river from the football stadium. Robert would probably know.

Robert Soko: I’m from Zenica, basically. But of course, I know Sarajevo as well.

Robert Rigney: We have spoken to various people like, Goran Bregović, Dr. Nele Krajalić, Srđan Gino Jevđević, for instance, about the heady climate that was Sarajevo at the end of the eighties. There was a lot going on in terms of culture. What was your impression of Sarajevo? Was it a provincial backwater, or was it a place where a lot of things were happening culturally?

Aleksandar Hemon: It was not a backwater. I thought it was the most interesting place in Yugoslavia at the time. The other cities were pretty good. Good things were happening there. It was this period in Yugoslavia between Tito’s death and the beginning of the war where there was a general liberalization and also people coming of age, like my generation, which meant music, movies, books, radio, press. It all came together. Bregović belonged to the time before that. He kind of tagged along. But he was not at the forefront of anything, ever. I detested him, and I have detested him since I was a teenager.

In any case, there was this window in between communism and fascism, where it seemed possible – everything seemed possible – including politically, to create some kind of different social order, bordering socialism. We felt that with culture and music we could win the battle. But they had the army and the police and the institutions, and the money and a history of fascist ideas in certain parts, and all that. So, we lost the battle.

But at the time it was very exciting. In many ways we were at the forefront. We had been neglected because of Bosnia’s complex political structure and there was a tighter control over Bosnian Sarajevo. And once it was loosened there was this potential that came up. And I loved it. Obviously, I love Bosnia and Sarajevo. It has never been mono-ethnic. It was always multicultural, multilingual.

It is also importantly, I think – and not completely positively – but it was rapidly urbanized after WWII. It was a backwater, and then it wasn’t. Because it was industrialized. There were these state companies that were doing very well, which allowed the middle class to rise. I’m a product of the middle class. But the houses had dirt floors. So that the kids had ideas. And it all came together at the same time. Even Krajalić, who is a fascist now, but he was a part of that. And Bregović, who was just trying to tag along with his instinct. But it was amazing. And then little by little, as with everything it Yugoslavia, it started coming apart.

Robert Rigney: And your leaving Bosnia was a direct result of the war?

Aleksandar Hemon: I was invited another time to go to the States for a month, organized by the United States Information Agency. They used to have cultural centers all over the world. The Republicans shot that down. But back in the day there was an American cultural center in Sarajevo and in Belgrade and Zagreb and in other places. They would invite people from all over the world to come on a trip to the United States for a month to facilitate cultural exchanges. Cultural engineers would be invited, too. It was scientific, too. So I came along with that for a month. I was a young journalist in the eighties. And I went around the United States. And after that I stayed on to see some friends in Chicago. That was my last stop. I was supposed to go back to Sarajevo May 1 in 1992. And May 2 the siege completely closed it down. By that time I had decided to stay in Chicago.

Robert Rigney: How was that for you when the war broke out, you being in America, presumably watching the news, anxious about friends and family?

Aleksandar Hemon: All that. There was no internet. So I was watching CNN which was broadcasting the same story seventy times a day. Rumors were coursing about. There was internet technically. But it was not available to the populous. So there was no way to be in touch. I wasn’t planning to stay. I had no money and no clothes, no immigration status. So eventually I had to find a job, a low-wage job, for Greenpeace; I was a canvasser. Eventually I started writing in English.

Robert Rigney: This comes forth in your novel, Nowhere Man. Also in the novel there is this incident where a guy from ex-Yugoslavia – a Bosnian Serb, and a nationalist – makes the protagonist an overture of friendship, which is rebuffed. How was it for you when in the States, you met people from Bosnia – Muslims, Serbs, Croats – did you instinctively embrace these people, or were you rather more stand-offish?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, in my mind, ethnicity is not that important. Ethnicity does not result in a political position. If your call yourself a Bosnian, it has nothing to do with ethnicity; it is a matter of citizenship. It’s like calling yourself an American. It implies a sense of ethics and politics. I’m of, what is called, “a mixed heritage”. Whatever that means. I hate that term. “Mixed marriage,” even. My father is from a Ukrainian speaking family. But he and all of his siblings were born in Bosnia. My grandparents from my father’s side were born in today’s Ukraine. They came to Bosnia at the time of the Austro-Hungarian empire. My mother calls herself to this day a Yugoslav and a Bosnian. And they always lived on this side of the river Drina. The other side is Serbia. They were progressive. My oldest uncle was in the Partisans. My mother has always been a communist. I’m a leftist progressive. So, I have always been Bosnian and Yugoslav. Actually, when it all fell apart I was calling myself a Ukrainian to increase the number of Ukrainians in Bosnia. There were only five.

The point is, though, if people declared themselves as Bosnian, I would hang out with them. They could be a Bosnian Serb or Bosnian Croat or whatever. In Chicago there was a lot of immigration stemming from WWII and the fascists. In some neighborhoods you could tell from signs and flags who was who. I tried to stay away from all that.

In the mid-nineties when the war started, the Bosnian refugees started coming to the United States and a lot of them came to Chicago. A lot of them came to the neighborhood where I was living, Edgewater. The rent was cheap. I looked out the window one day and I saw a Bosnian family walking down the street. It was the typical Bosnian family formation: the man at the front and in the wings the sons and the woman behind. It was like a flock of Bosnians. I saw them through the window and I instantly knew they were Bosnians. There was just the formation to go on; there were no other signs.

So they all landed in my neighborhood and elsewhere in Chicago, including some of the people I had known from before. I started hanging out with them and doing different thngs with them. Those were refugees, people who had been in concentration camps, who were, as the euphemism goes, “ethnically cleansed”. They were traumatized much more and much differently than I was. I had a job and I knew the language and all that. So I didn’t spend my days in these circles. But I would meet them and exchange words with them and was hanging out with them.

Robert Rigney: In talking to Srđan Gino Jevđević of Seattle ethno-punk band Kulturshock, he described the woeful ignorance of a lot of Americans with regards to the geography of East Europe, specifically ex-Yugoslavia. Did you find that a lot of Americans were misinformed about the basic facts of ex-Yugoslavia?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, it depended on who you talked to. The conflict was on the front pages. And American people read newspapers. Not just Twitter. So, it was on the front pages and in the news all the time. It was the biggest war in Europe since WWII. However, people didn’t know the details. They didn’t know exactly where Yugoslavia was, or where Bosnia was. They knew it was out there somewhere. I didn’t often encounter total ignorance. More confusion.

When I was canvassing people would ask me where I was from. Some people would know, and they would know a lot. Some people confused Yugoslavia with Slovakia. I once – because I was speaking English, obviously – a Serb guy invited me in and unfolded a map of Serbia from the fifteenth century and explained to me why the Serb position was the right position, and that there was a world-wide conspiracy against the Serbs going round.

Robert Rigney: This guy pops up in Nowhere Man.

Aleksandar Hemon: Exactly. And I would go out and go to parties and people would ask me where I was from. I would say, “Bosnia”. And they would ask me to “explain it simply,” what was happening. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to party and get laid or whatever. Eventually, I would say that I was Ukrainian. A few times – as in Nowhere Man – this I remember, I said was from Luxemburg, because everyone had heard of it, but no one knew where it was. Probably the president doesn’t know where it is. Trump doesn’t know where it is, and will never know. So, it got to the point that I didn’t want to explain anymore.

Robert Rigney: Let’s talk about music because time is short. Music has probably played a role in your life since your teenage years in Bosnia. I’m sure you came across – and Brega is the best example – this “Balkan Beats” phenomenon, putting beats to folk music. What’s been your take on this stylistic direction?

Aleksandar Hemon: There is turbo-folk, which is folk to beats. That was the music of war, though it is a simplification. It’s not the beats. It’s using electronic instruments to make music, which makes it cheaper and you don’t need an extensive studio or a genius accordion player, which was what you needed in the old way, the sevdah way. In Socialism, the state institutions, as their duty, saw to it that people’s heritage was preserved. So the ethnographers and ethnomusicologists would record their catalogue in various versions. Damir, as you well know, his father and his grandfather were involved in that. A canon was established of Bosnian recordings. There were some recordings by ethnomusicologists earlier, but much of that was recorded in Socialism. It required an orchestra and all of that sort of infrastructure. And because I was a punk kid, I thought, “Eh, all of that is shit! I don’t care about these peasants!” And then it became worse, because now I love it. But turbo-folk kind of simplified all of that. It was folk music that was a derivation of traditional music, which I detested.

But I was DJing with someone who was much younger than me, whose genre was break-beats. She started mixing in Seka Aleksić, and the kids went crazy. While I appreciate, intellectually what they were doing, I have no tolerance for stuff like that.

Balkan Beat can mean a lot of things. When I was young we would tell this story about how a Paris symphony going to perform a traditional piece of Macedonian music, but their percussionist fell ill and they couldn’t find anyone who could play in his style and then they found this Macedonian nigger, who said, “Yeah, I’ll do it.”

In the eighties, in Yugoslav pop music there was this hybrid transformative influx of traditional beats. Like bands like Haustor and Idoli. Also the eighties was the time of so-called World Music. Talking Heads and Paul Simon. So there was this traditional influence in Yugoslav pop and rock music. But it was used differently. It wasn’t just looping, or sampling. It was integrated. We all liked it. So there was a different sort of interest in traditional idioms. And it became cool.

Robert Rigney: Did your coming round to traditional Balkan music coincide with your discovering Damir Imamović?

Aleksandar Hemon: It pre-existed that. Some of the songs everyone knew. You would get drunk at a party and you were in a certain state of mind, you would sing them. They also recorded these songs, and you could hear them on the radio, and so on. And that was reacted during the war, right?

It was in reaction to the war, right? Sevdah. It became important to us suddenly, us realizing that this is valuable, which they were trying to destroy. It was just out there, and you were thinking it would last forever. And you said, “I’d rather listen to punk.” They set out to destroy all that. And then you would get to thinking, but I don’t want to stand by and let that happen. There was a whole new generation. Damir. Amira. They were young, cool kids. They listened to rock and pop music, but thought: “I can do this.”

Mostar Sevdah Reunion was the breakout point. They did it in a way that is cool. It wasn’t the official radio orchestra with an accordion…and the orchestra there, sitting in suits, in a studio, playing this. It became valuable and cool. They revived it.

And then Damir carried it further and further. What Damir has done is discover the “queer notes” in sevdah. So, reinterpreting – not reinterpreting – but opening up that space. What we didn’t like about sevdah was that it was traditional. We were young kids interested in social and cultural change. Everything traditional was suspect. Not only my parents’ stuff, but my grand parents’. I loved them all, but after the war. It assumed a different value, before the war and after the war. The kids took to it.

Robert Rigney: The thing about a lot of sevdah music is that it had a lot to do with star-crossed lovers who were stymied by a conservative society, prevented from living out their love for each other. Today, in an atmosphere of instant gratification, the songs seem antiquated and foreign. But for queers in Bosnia it may be different. Society is still constructed so that such same-sex relationships are frowned upon. So that in the hands of one of them – of a Damir or Bozo Vreco – a sevdah song, given its new queer subtext, takes on – or still has – an added relevance.

Aleksandar Hemon: Robert (Soko), you probably know this song, this very famous Bosnian song, “Snijeg pada na behar, na voće.” It’s a very traditional song. It’s one of the classic sevdah songs. My parents sang it. Everyone has song it. It’s an unofficial anthem of the queer pop movement of Bosnia. At the first Pride in Sarajevo, Damir sang this song.

Robert Soko: I had no idea. There was also Himzo Polovina, who was gay.

Aleksandar Hemon: It was always very encoded. I knew his son. But yes, it was always there. It was this sort of unrequited desire among queer people but also amongst women. Arranged marriages crossed all ethnic lines. There was a lot of prohibition, a lot of control of love and desire. Sevdah was a way out of it. Some queer people can therefore identify with these songs. The way Mostar Sevdah, Amira and Damir open up these things. People lose their minds in these songs because they can’t see the neck of a girl.

With regards to Damir and my collaboration – I had already known him from the past – but it was I who approached him. It turned out wee had a lot of common friends. I loved his music. The difference with the new generation was not that they were trying to preserve it.

The old way – as it was presented on radio and television – was to preserve the songs. They were not, of course, preserving it, rather they were modernizing it. The accordion was not a traditional sevdah instrument, and so on. But, officially they were preserving it. All the while, they were updating it.

Damir has done amazing work in that regard.

So when I was writing my book, The World and All That It Holds, which is about queer love between two Bosnians, it occurred to me, insofar as they sing songs to each other – sevdah songs, but also Sephardic songs – which really overlap – and the unofficial song of Sarjevo is “Kad Ja Podjoh Na Bembasu” is a Sephardic song. Sephardic music. But the words ae local. Anyway, they were singing songs in the novel. And my idea was, “What if Damir recorded some of those songs?”

So, I contacted him and proposed it to him half way through my first draught. He liked the idea. He started writing and recording some songs. He found some older versions of Sephardic songs – and also Bosnian songs – and reinterpreted them in his own way. He would send me demos. I would send him chapters. He would write a song, “Bejturan”, for instance, the lyrics written by a Bosnian refugee in Sweden.

Then I reintegrated those words, anachronistically into the novel. And he wrote a book about Osman, which is the name of one of the characters.

Because Folkways Smithsonian was trying to do something with him, I pitched this to them as an album. And we were trying to coordinate the album and the book, having to do with organizing a tour in the United States.

Robert Rigney: Did anything come of those plans?

Aleksandar Hemon: No. It wasn’t coordinated between my publisher and his publisher. But he might still come.

Robert Rigney: Speaking of The World and All That It Holds, to tell the truth, I am not a big fan of historical novels. I appreciate, rather, writing that is direct, unmediated, relating to things I have experienced in my life. But you wrote an historical novel, and I wanted to know, what is the trick in writing an historical novel?

Aleksandar Hemon: The material has to be modernized in some way. I can not compare my methods to some other -so-called – novel writers methods, just because I don’t know where they are. But one thing is that I ensure that the narrator is present in this time. It’s a particular point of view. It is not projected. It does not come from the position of historical authority, historian authority. Rather it is from the point of view of someone who is trying to figure it all out. Because for us in the Balkans history is continuous. To me there is a continuity there. So, whatever is in the book, it is continuous with this time. It’s not something that happened in the past that has no connection with this. Costumed people and so forth. That’s not what it’s all about.

Robert Rigney: In The World and All That It Holds, one of the main characters is Jewish. You have used other Jewish protagonists in your writing, though you yourself are not Jewish. What is it about the figure of a Jewish protagonist that resonates to you?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, in this particular book, he is Bosnian, and a part of the Bosnian landscape. And Pinto, my character, had been there since the 16th century. In Sarajevo. So, he’s not just Jewish, just like Osman is not just Muslim. There are layers of identity.

Having said that, the central fact of my life is displacement. No people have more stories of displacement than Jewish people. In many ways theirs is the template for displacement narratives. It starts in the fucking bible.

In this book, specifically, it all started with music, essentially. In the great eighties someone gave me a cassette tape called Memories of Sarajevo by a woman called Flora Jagoda. Flora Jagoda left Sarajevo in 1947 as a young Jewish woman, who had survived the Holocaust and ended up in Baltimore, and who sung songs of Sarajevo about Sephardic Jews to her children and grandchildren.

Eventually, in 1989 she was talked into recording those songs as an album. She recorded two albums, Memories of Sarajevo, which came to be known as Songs of my Grandmother. And she died a couple of years ago at the age of 96. Before the war I got hold of this recording, and I loved it so much because she sang in Ladino. But a lot of it was very much related to what I knew from Sarajevo; to sevdah. The harmonies, the scales. The way she pronounced certain sounds like people in Sarajevo pronounced them. To me, I just flipped. So, I imagned writing this book. These are some of the songs that Pinto sings to Osman. And I started being interest in the Jewish, Sephardic history of Sarajevo. And the fact that it was all wiped out. I know the old Jewish neighborhood, where the synagogue was, though it is barely marked.

And Socialism had it that the people who were killed were “the victims of fascism. There was no differentiation. It was one of the clumsy ways to cover up the inter-ethnic conflict that took place during WWII. There is a monument to the victims of fascism above Sarajevo. You have these walls and stones laid out like steps, the walls with the names of the victims. You have whole walls with the names of Jewish victims. “Victims of Fascism”. So their extermination was not owing to the Holocaust; it was “fascism”. They did it in the Soviet Union, too. That was the kind of narrative during Socialism. So, as a writer I wanted to recover that forgotten history. So that Jewish history was interesting for me insofar as it was also the history of Sarajevo.

Robert Šoko: The World and all that it Holds completely blew me away. I was curious about the feedback. Because the book was such a masterpiece that I asked myself would people in the Balkans get the message and what impact would it have on this culture here which is still being poisoned by a lot of prejudices and nationalisms.

Aleksandar Hemon: People in Bosnia and the region love me and I love them. But it’s also a self-selecting audience. Fascists don’t read me, let’s put it like that. They probably don’t know about me, because I don’t move in those circles. The people what do know me are people who think of Bosnia as the land of possibilities that was fucked up and who revel in the complexity of the place, which is what I love. That complexity came at a high price. There was a war and fascists tried to destroy it and still are trying to this day. But people who read my books identify with that idea: the complexity of Bosnia.

This interview is a part of our greater imagination aiming at completing a BalkanBeats Book.